The Modern House meets ... Rick Armiger

This week we met with Baltimore-born architectural modelmaker-to-the-stars Rick Armiger. Having founded Network Modelmakers in 1983, Rick has spent the last three decades honing his craft in London, and lists everyone from David Chipperfield to Zaha Hadid amongst his clients.

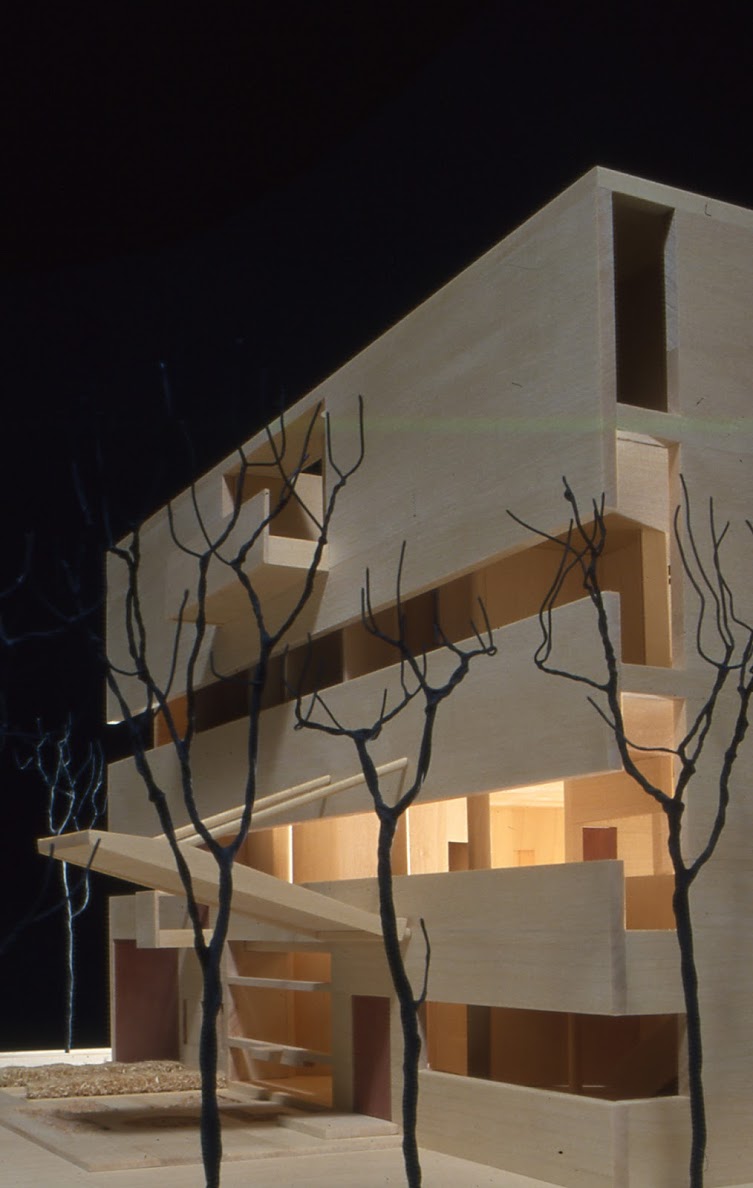

As a modelmaker, Rick is involved in projects in the very early stages, tasked with bringing the architect’s initial two-dimensional plans to life. Amongst his most recent projects was a model for the new Design Museum – set to reopen to the public later this month in a former 1960s building on Kensington High Street. Rick’s model was an integral part of the initial planing process, providing a catalyst for John Pawson’s design for the interior spaces.

Rick’s own apartment in Wesley Square – an award-winning private garden square in Ladbroke Grove – is currently on the market with The Modern House. Wesley Square was designed in 1976 by celebrated architects Terry Farrell and Nicholas Grimshaw, both of whom Rick has completed projects for. The most high profile of these was perhaps Grimshaw’s Eden Project, completed in 2000, for which Rick made the initial model.

We caught up with Rick to hear about his first forays into modelmaking in 1970s Baltimore, and to catch up on some of his most exciting recent work.

What inspired your interest in modern architecture and design?

I blame Eero Saarinen.

I’d seen his Detroit campus for the General Motors Technical Center, Michigan, and was intrigued by that, but a first trip flying into TWA Idlewild (now JFK Airport) was pretty seminal.

Little me, all wobbly and wide-eyed with the excitement of it all, asked a stewardess, ‘Miss … who designed this?’, and I was probably only ten years old, but something clicked. I began to connect the dots. My mother worked in the local library and, responding to my enthusiasm for something other than cars, brought me home a pile of Arts & Architecture magazines.

Like mothers do, she’d seen my future. In my studio I still have this great photo of Saarinen inside a huge TWA Idlewild study model. To me it’s poetic.

How did you first get into it?

That’s a long story. But in short, many great mentors. With guidance from them, I was lucky to find that ideal-for-me marriage of modern architecture with my education in painting and sculpture. That ‘perfect marriage’ led me to the UK to meet the elder statesman of mentor makers; George Rome Innes at Arup.

The longer version begins back in Baltimore, in the US, where I grew up. My extended family of friends’ parents were all architects or designers. All were hugely influential, and one had a Marcel Breuer house (by then-partner Bill Landsberg).

‘Mother Betty’, who commissioned the Breuer house with her husband after the war, was a medical modeller of prosthetics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, making her extra influential to me in a very specific way. Also within this circle was ‘Uncle’ Robert, an illustrator at the Smithsonian, and ‘Uncle’ Bill who was the curator at the Renwick Gallery. All these, my ‘adopters’, steered me to New York, then Boston and Cambridge Seven Associates (C7A) where my career began properly.

The critical point for me, whilst at C7A, was when a sweet graphic designer, Karen Lewis, told me about George Rome Innes’s model architecture unit at what was then called the Medway and Maidstone College of Art and Design. I applied and got a place, and upon graduation was invited by the architect Sir Hugh Casson to set up his in-house model shop in Thurloe Place, across the from V&A.

Tell us a bit about Network Modelmakers. Who are your most well known clients?

I founded Network Modelmakers in 1983, and our initial life in Spitalfields had three key clients, all of whom I met when I was teaching at Chelsea School of Art; Sebastian de Ferranti, Jan Kaplicky and David Chipperfield. Soon after we also counted Eva Jiricna, Jeremy Dixon, Ed Jones amongst our clients. Then all the Lords and Sirs, and with the first boom, many more.

The other day my sweetheart said, “Honey, except for U and X and Y, you have every letter in the alphabet covered from Alsop to Zaha!”

Where has your work been exhibited?

All the usual suspects really; Venice Biennale, the Architecture Foundation, the Design Museum, the Architectural Association, the V&A, the Soane Museum, the RIBA, as well as lots overseas. In 34 years, 34 Network models were selected for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, too. So that’s nice.

What’s the most exciting project you’ve been involved with?

What excites me now is a new strand or side to the work, ‘Blindside Models’. These are charitably funded models for the blind and visually impaired. Not those small cast-bronze crude things, but large, high-detail timber models whereby you learn to understand the majesty, the voids, structure, spires and whatnot of the building, simply by feel.

Tell us about your work for the new Design Museum?

I’ve long felt close to what Sir Terence Conran was doing, and what he was encouraging, with his initial design for the museum. If you think back to the Thatcher years when the museum was first established, here was this seemingly lone voice shouting as loud and for as long as he could about the value of quality design, architecture and craftsmanship. For me personally, it felt heroic.

Terence Conran always put his money where his mouth was, then and now. Fast forward, and I reckoned it was time I did too. In the economic mayhem after 2009, I could hardly afford to fund an entire mega-model alone, but I did manage to fully fund one key element when I was asked to work on the project; the new building’s most bewildering component – that madly complex paraboloid 25-ton copper roof. My model helped kick-start things three dimensionally, physically, and thus, voilà – the design within for the new space by John Pawson, which will be unveiled later this month.