A Voyage around my Grandfather by Matt Gibberd

First written for The Sunday Telegraph magazine in 2010 by our Founding Director Matt Gibberd, this article tells the story of his grandfather Sir Frederick Gibberd – a master of British modernism:

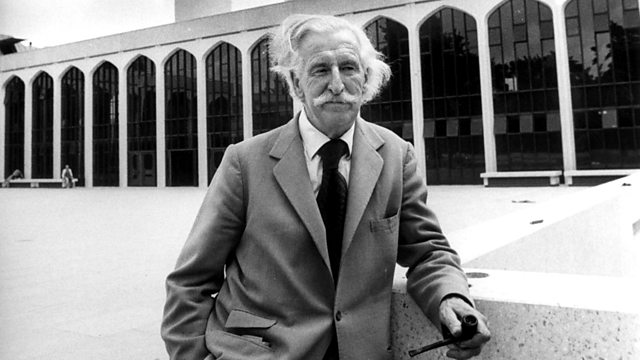

To the good people of Liverpool, he is Sir Frederick Gibberd, the architect who gave them their most iconic landmark. But, to me, he will always be Grandpa Whiskers, a sobriquet that referred to his uncommonly hirsute visage. I was only six years old when my grandfather died in 1984, but his influence on my life has been considerable.

My overriding memory is of a relaxed affable fellow pottering around in his garden on a sunny day, trowel in hand, pipe between lips. Freddie never went anywhere without his pipe, and the house he designed for himself in Harlow, Essex, lingered beneath a cumulus of Three Nuns tobacco smoke. It was not an uncommon occurrence for him to absent-mindedly drop his pipe into his coat pocket and set fire to himself. But humorous ‘smoking jackets’ aside, he could also be quite a cantankerous figure, not always loyal, but blessed with prodigious talent and ambition to match.

Just over 100 years after his birth, the time seems right to reappraise the career of one of Britain’s most influential Modern Movement architects. Freddie was born in Coventry, the eldest of five boys. There was no design background in his family. ‘The turning point was when my father built the billiard room,’ he once said. ‘It had a very unpleasant terracotta coping around it, and my father thought it should have been battlemented. When he wouldn’t pay the final account, the contractor said he should have appointed an architect. That’s how I learned what an architect does.’ Freddie went on to design a modern house for his parents whilst studying architecture at the Birmingham School of Art. But the building that launched his career was Pullman Court in Streatham, south London, designed at the precocious age of 23. The commission came after he picked up a girl at a dance hall, who, as luck would have it, was the secretary of a property tycoon.

Now Grade-II listed, Pullman Court is an essay in the International Style as propounded by Le Corbusier and the German gentlemen of the Bauhaus. It was undoubtedly a radical building. Each flat was equipped with furniture specially designed to fit the space, as well as a state-of-the-art sound system and modern electric fire. Freddie was a clever colourist and the Pullman Court render originally sported a suave scheme of brown, blue and cream. It has since been repainted in standard-issue white: we like our Modernism in monochrome, a prejudice that stems, one suspects, from seeing these buildings in black-and-white photographs.

Such was the success of Pullman Court that my grandfather was asked to design a succession of London apartment blocks, including Park Court in Sydenham, Ellington Court in Southgate and the Somerford Estate in Hackney. He became known as the ‘flat architect’, and co-authored a book on the subject with his friend FRS Yorke. The Modern Flat remains one of the defining publications of the age. ‘We believe,’ they wrote, ‘that the problem of housing cannot be solved by the provision of millions of little cottages scattered over the face of the country.’ Freddie was of the view that careful town planning would help free up the landscape: far better to have a succession of carefully conceived high-density housing blocks separated by swathes of open land.

My grandfather was a member of MARS (the Modern Architectural Research Society), alongside Serge Chermayeff, Wells Coates and Berthold Lubetkin, and later a Royal Academician. But this was long before the notion of the ‘starchitect’ was born. Frustrated by the second-class status of his chosen profession, he wrote: ‘One sees articles in the press or hears of people talking about books, wireless, gold, films, gardening and a host of other things, but never about architecture. This is altogether deplorable, because the design of buildings is an activity at which the English have excelled and still do excel.’ In fact, were he in practice today, it is likely that Frederick Gibberd would be as much a part of the public consciousness as Richard Rogers. The parallel seems particularly pertinent given Rogers’ recent completion of Terminal Five at Heathrow: my grandfather designed the original airport buildings, some of which are now listed.

Freddie was unfit for service during World War II because he had only one kidney, so he took up the position of principal at the Architectural Association in London. Among his pupils were Philip Powell, later of Powell & Moya, and his namesake Geoffry Powell, who co-designed the Barbican in London. Freddie also studied town planning during this period and, in 1947, was appointed as planner for the new town of Harlow, where his talent for landscape design found its greatest expression. He later bought himself and his wife, Thea, a house with land on the edge of the town, and set about creating one of his most enduring legacies: his own garden. Speaking on Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, he declared gardening was the only way in which he could ‘design without using a drawing board’. Now open to the public, the Gibberd Garden is one of Britain’s great outdoor spaces. Freddie and Thea worked on it tirelessly, he cogitating over vistas, she providing inspirational planting schemes.

A journalist once visited the house for an interview and caught Freddie backing out of a border in his civvies. Mistaking him for the gardener, the journalist enquired after the architect’s whereabouts. My grandfather duly doffed his cap and told the man to carry on up the path and ring the bell, before hurtling through the kitchen entrance and opening the front door with a flourish and a grin.

For me as a toddler, the garden at Harlow was a source of great adventure. My brother and I used to scuttle around the neoclassical columns that Grandpa Whiskers had salvaged from Nash’s Coutts Bank on the Strand (to which he contributed a spectacular modern atrium in 1978). We and our cousins would also indulge in war games on the moated ‘castle’ he had built specially for us from bits of wood. He was an early recycler. He once arrived at Harlow and told Thea, eyes twinkling, that he had brought a pair of girlfriends for lunch. She dutifully went out to greet them, to be met by the sight of two carved angels he had purloined from a church, sitting in the back of his Bentley. Freddie liked cars. In his youth, Coventry was the centre of the British motor industry and he had flirted with the idea of becoming a vehicle designer. I particularly remember his vintage drophead Rolls-Royce. Ignoring the fact that we had to stop for petrol every few yards, I would obsess over the car’s sultry black curves and lashings of leather. I have a book that he wrote about Harlow with a hand-written message inside that reads: ‘To Matt, for when he grows up, from Grandpa Black Car.’

As a boy, my grandfather was exactly that to me: an important member of the family. That he should also be deemed an important member of society only dawned on me when I visited his most famous building: the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King in Liverpool. A Catholic counterpoint to Giles Gilbert Scott’s Anglican cathedral nearby, it has been affectionately dubbed Paddy’s Wigwam owing to its distinctive crown-of-thorns silhouette. Whereas Scott’s building dazzles the visitor with its gargantuan scale, the Gibberd cathedral achieves the same effect using economy of form and fine detailing. My father took me up from London to see it and the visit was one of the most affecting experiences of my young life.

The circular interior of the cathedral is lit through large stained-glass lanterns designed by John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens. Freddie was a great supporter of contemporary artists, and he amassed a very fine private collection. He set himself the parameters that each picture had to be by a living British artist and either a watercolour, drawing or print. Many of the works, by the likes of Graham Sutherland and Elisabeth Frink, he subsequently donated to the town of Harlow, where they are housed in the purpose-built Gibberd Gallery. Henry Moore was a good friend, and would often come for lunch. During one visit, the artist made some farmyard animals out of Plasticine for my aunt Sophie; as the gathered throng began, in their minds, to estimate the collective value of these ‘sculptures’, he squashed them flat with his palm.

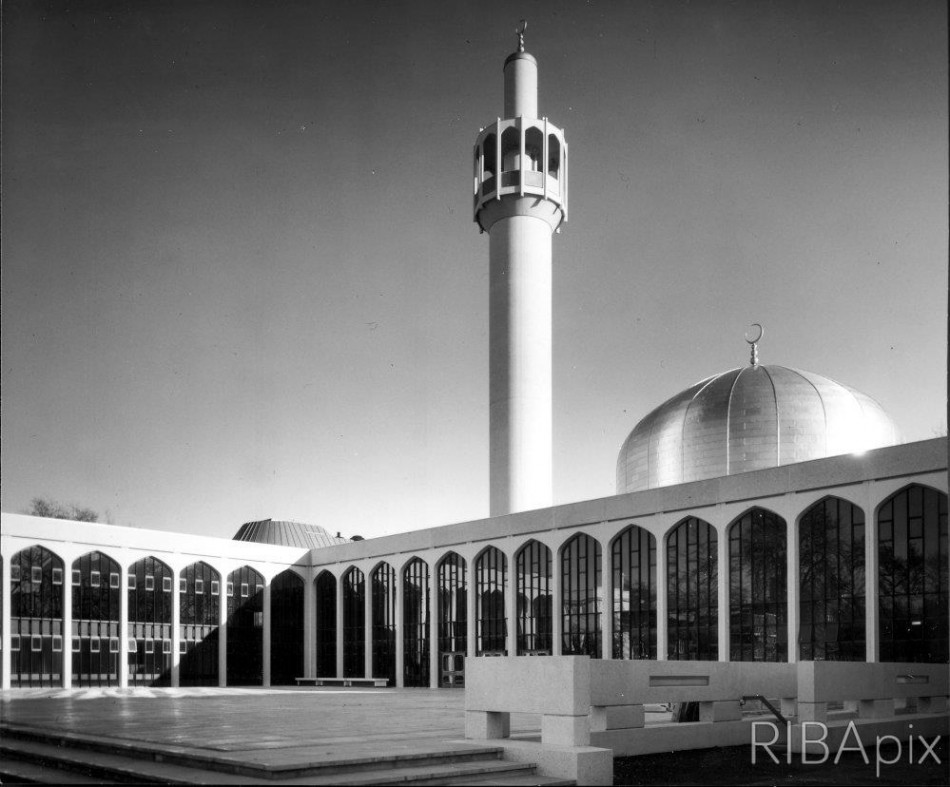

Although always careful not to be typecast, Freddie designed a number of significant religious buildings. As well as the cathedral in Liverpool, there was the Sixties monastery at Douai Abbey in Berkshire, and the lustrously domed London Central Mosque beside Regent’s Park. He always joked that he had hedged his bets for the afterlife. This mischievous sense of humour often surfaced at the unlikeliest moments: his daughter Cate recalls that, while waiting to receive his knighthood at Buckingham Palace in 1967, he sang along to the music and pulled rude faces at the family.

My grandfather retired in 1978, but continued to act as a consultant to the practice that still bears his name. Then in his seventies, he would accompany us on family holidays to Cornwall. Whereas we stayed in a rented cottage near the beach, he insisted on checking in to the de luxe hotel up the road. He always took his drawing board with him; like most architects, he could never switch off. He would have been delighted that his obsession with the built environment has been transmitted through the generations. My father has forged a successful career as an architect and one of my cousins also works in the profession. As for me, as well as being a writer on architecture, I am a director of The Modern House, a company that sells architecturally significant buildings. I sometimes wish my grandfather was still alive, so that I could absorb from him all the lessons he learnt. But then I check myself and think: he’s not Sir Frederick Gibberd, he’s Grandpa Whiskers. And that’s just fine with me.

Photographs of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral and London Central Mosque: RIBA Library Photographs Collection